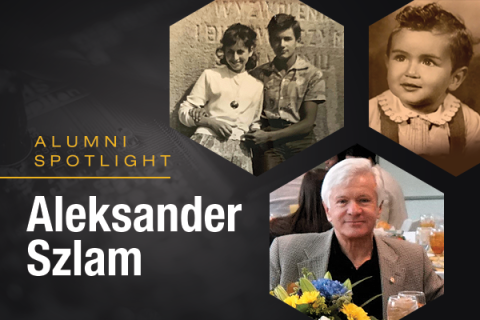

Alumnus Aleksander (Alek) Szlam (BSEE ‘74, MSEE ’80) has a life story that would make a great Hollywood screen play—part coming to America, part love story, part rags to riches.

Alumnus Aleksander (Alek) Szlam (BSEE ‘74, MSEE ’80) has a life story that would make a great Hollywood screen play—part coming to America, part love story, part rags to riches. Intermingled with it all is the tenacity, creativity, and intellect that perfectly illustrates what it means to be a Ramblin’ Wreck.

Born in 1951, Szlam grew up in a city called Wroclaw in southwest Poland. His parents were Holocaust survivors. His mother was among the 5% of Romanian Jews who survived the Transnistria Ghetto—the largest concentration of Jews in the world. Their experience impacted the way they viewed the world thereafter.

“My parents’ survival was a miracle and they were grateful. They showed this through their deeds. I grew up experiencing the empathy and caring they had for their community and understood the calling,” said Alek.

Alek grew up during a time of political strife and economic depression as Soviet Communism moved into Poland after World War II. Despite social unrest and continued anti-Semitism, life went on more or less normally for Alek. He developed a passion for composing music and playing guitar in a local pop group, which left little time for study. He attended school, squeezing by with average grades.

When he was 14 years old, he went to a Jewish summer camp where he met a cheerful, brown-eyed girl named Halina Ajlen. They became good friends and corresponded for a couple of years, even visiting each other’s towns. Eventually, they lost touch.

Rising anti-Semitism in 1960s communist Poland eventually culminated in a mass emigration of Polish Jews. The government encouraged Jews to leave while taking away their valuables, diplomas, and even their citizenship. Alek and his entire extended family of aunts, uncles, and cousins left Poland for Vienna, Austria in 1969 hoping for a better life. It was in Vienna that they were connected to the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) and given options for a new country to call home. Alek’s family decided on the United States. HIAS made all the travel and living arrangements for them as well as locating sponsors from the Jewish Federation of Greater Atlanta who assisted with their immigration.

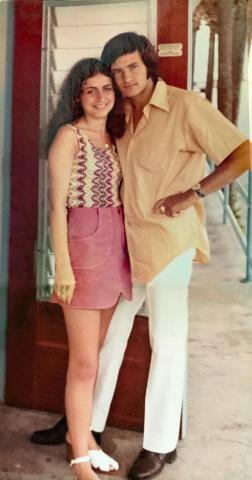

Before arriving in the US, the family traveled to Rome, Italy where they waited several months for proper vetting, entry documentation, and visas. It was on a train platform in Vienna that Alek and Halina reunited. Halina’s family was also going to America and ended up on the same train destined for Rome. Throughout the journey, Halina and Alek reflected on their lives in Poland and wondered about the uncertainties that lay ahead.

In Rome, Alek and Halina became inseparable. They skipped their English classes and explored the city. “We had no money, so we just walked and walked for miles and miles. If we did get some pocket change, we spent it on a cappuccino or maybe went to the movies to see an American western,” said Alek.

It was during this time that they began to fall in love.

In April 1970, both families received immigration documents at the same time and boarded the same flight to New York.

“So we were sitting next to each other on the plane,” reminisces Alek, “And we were wondering aloud – ‘Wow, America—what will it be like?’ We were leaving the gray and black world of Communism forever.”

In New York, the families parted ways—Halina’s family went to Pittsburgh to settle and Alek’s family went to Atlanta. But this time they wouldn’t lose touch.

Upon their arrival, Alek and his family were immediately connected to members of the Jewish community in Atlanta. One of their sponsors was Mrs. Clara Eisenstein, who like his parents, was a Holocaust survivor from Poland. Alek found work as a draftsman and estimator in an industrial engineering firm. Mrs. Eisenstein saw Alek’s potential, so she took him to visit Jim Dull, the dean of students at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

“She took me to Tech Tower and she was speaking to Dean Dull for a long time,” said Alek. “I couldn’t understand any of the conversation and then she started to cry. She turned to me with mascara running down her face, pulled me to the side, and said in Polish, ‘You’re being admitted on probation—so you better study hard or else!’”

With no high school diploma, no SAT scores, and only the most rudimentary command of English, Alek began his studies in the spring of 1971.

Alek, who says it was a “different time” and acknowledges that it takes far more than a persuasive Jewish lady to get into Georgia Tech these days, appreciates the chance he was given. “Right away I had a connection to Tech that goes beyond most. It was really special,” said Alek.

Due to his experience playing in bands and tinkering with equipment like amplifiers and speakers, he decided to major in electrical engineering. He knew he had to do well, so he hit the books learning English while also studying math, physics, circuit design, digital signal processing, and computer programming. Alek finished his bachelor’s degree in 11 quarters with highest honors and matriculated in March 1974. One quarter before graduating, Alek and Halina were married.

His first job was with an industrial engineering firm that built paper mills. He ended up hating it. As he became proficient in the daily tasks, he realized the work had little to do with the electronics and software concepts he learned at Georgia Tech.

Alek, who calls himself “impatient,” went through a series of jobs that he quickly mastered and then almost as quickly got bored with, some lasting only a few months. A job at NCR in Columbia, South Carolina introduced him to applied electronics and microprocessor design, but it wasn’t until he landed at Solid State Systems in Marietta, Georgia, in 1978 that he found the right balance between challenging work, creativity and design, and enough time to spend with his growing family (daughter Juliette was born in 1976 and son David was born in 1979).

At Solid State Systems, Alek designed Private Branch Exchange (PBX) telephone systems. One client was Wisconsin Public Service, Power, and Gas. They needed a computerized system that would dispatch maintenance crews around the clock in emergency situations. A new solution would ideally replace the current method in which multiple dispatchers manually dial from a calling tree, with an intelligent, automated system. Solid State Systems rejected the project on the grounds that it couldn’t be done, but Alek was determined to figure out how to automate emergency dispatching, so he took it on in his spare time.

Once he came up with a design and built the hardware and software, he had the system repeatedly call Halina and their neighbors as a test. Then there was the moment of truth. He installed what he called his “Telecomputer” at the client site. During the first test, the Telecomputer dialed out correctly, but when a person answered, the system did not recognize it, therefore, it was unable to play the emergency voice message.

“Failure teaches you everything. I was furious [that it didn’t work]. I apologized profusely and changed the software so that the system would work manually. On the flight home, it suddenly all became clear. I realized what went wrong. There on the plane, I invented ‘Answer Detection’,” said Alek.

Once back home, Alek designed and built filter circuitry for each telephone line, wrote real-time signal analysis code, and modified the system’s software to process outgoing phone calls. Ringing patterns were captured, saved, and analyzed and this became known as “Answer Detection“.

Back in Wisconsin with his new and improved invention, something fortuitous happened. While testing outbound calls, Alek heard the telephone next to him ringing. The line was connected to an oscilloscope and he saw a series of modulated waves. Using his newly installed circuit and firmware, he discovered that the waves represented the phone number of the caller.

“That’s how what is now known as Caller ID was born,” said Alek. He later developed and patented a process that uses the phone number to look up a person’s information and display it on an agent’s terminal.

With a promising new technology and several patents, Alek decided it was time to start his own company. Melita International, which is named after his sister, was founded in 1983. It employed one software engineer, in addition to Alek and Halina. Halina, whose career began in medical research, quickly jumped into multiple roles for the fledgling company including operations, human resources, accounting and price negotiations, system assembly, and facility management.

The company’s first product was a fully automated outbound and inbound call processing system, initially called the Expedialer and later renamed and marketed as Sprintel. Some of Sprintel’s first customers were school systems that used it to notify parents when students were absent.

As the company and its technologies matured, Alek filed dozens of patents and drove the call center and customer interaction management industry by establishing standards including answer detection, predictive dialing, call blending, screen pops/Caller ID, intelligent “on hold” management with call routing, Computer Telephony Integrations (CTI), and more. Today, Caller ID is used by hundreds of millions of people around the globe for SMS/texting and a multitude of mobile communications services.

Halina continued her leadership in business operations for the company as it grew to about 500 employees. Melita went public on NASDAQ in 1997. Growth and profits were phenomenal with Melita’s innovative technologies supporting call centers in 45 different countries. After a brief merger in 2001 and further acquisition in 2003, Melita employees and operations are now housed under Aspect Software, Inc.

Today, most of the world’s contact centers are built on Melita’s technologies, providing employment to millions of people across the globe. These innovations help mobile users interact, assist charities with collecting donations, alert communities during emergencies, and provide superior customer services for big and small companies.

These days, Alek and Halina are enjoying time spent with their children Juliette and David, and their four grandchildren. They support various charities and philanthropic projects, particularly those promoting education and the abolishment of anti-Semitism. Alek is a board member for his alma mater, Georgia Tech’s School of Electrical and Computer Engineering; the Chopin Society of Atlanta; and Conexx, an organization that connects Americans and Israelis via business. Both Alek and Halina are avid supporters of Georgia Tech scholarship programs, the Jewish Federation of Greater Atlanta, the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum, and Temima High School, among others.

Alek, an avid road cyclist since 2003, participates in numerous local and international bicycling events. While Alek is now technically retired, he’s still innovating and dabbling in patents. But the bulk of his time is spent mentoring students and entrepreneurs and working with organizations that “focus on shaping a safer, more tolerant, and more peaceful world.”

When asked what advice he would give a current Georgia Tech engineering student, he said, “Think 20+ years into the future of what our world may need the most. Document your ideas. Start designing, prototyping, and validating them now at Tech’s multidisciplinary makerspace labs. Worry less about obtaining the highest grades. Enjoy campus. Interact and collaborate with other students. Spend some time just relaxing! And keep on smiling….”

Additional Images